The painting tradition of Vraja

kalānām pravaram citram dharma-kāmārtha-mokshadam / mangalyam prathamam caitadgrihe yatra pratishthitam

The art of painting is superior among all arts. It bestows righteousness, (success of) work, wealth and liberation. The house in which (this art) is upheld will be fortunate in the first place.

Citra-sūtram, Vishnudharmottara Purana 3.43.38

The art of miniature painting in North India in the form in which it is known today was essentially shaped during the 15th/16th centuries. From the 15th century onwards, in the wake of the current of Hindu and especially Vaishnava devotionalism that entered northern India from the south and east, Hindi literature as well as the practice of painting received their major inspiration from the newly awakened religious tradition. The 15th century is thus seen as the period of revival and re-establishment for the arts on the whole, including music, poetry, fine arts and architecture.

Since the influx of Vaishnava bhakti was primarily Krishnaite, and moreover with Lord Krishna’s legendary homeland Vraja located right at the heart of northern India, it is only natural that the Krishna theme came to be the principal source of inspiration for the various streams of Vaishnava art in North India. In the same manner as the Vaishnava poet-singers vocalized their devotional experiences in their poetic compositions describing and glorifying Lord Krishna’s transcendental play, the divine couple Krishna and Radha and their pastimes occupied the center of the artists’ imagination. Miniature paintings of the 15th/16th centuries consequently focus on the devotional aspect in the context of the Radha-Krishna theme; further thematic cycles include the musically inspired ragamala paintings as well as paintings based upon literary texts.

The style of North Indian miniature painting which was initiated during the 15th century in Vraja has been preserved to the present day and is practiced even now. Its pure, original form - referred to as the Vraja style - evolved from the Vaishnava temples. Under the reign of the art-loving Mughal emperor Akbar, many painters from Vraja took employment with the Mughal court, and an individual, secular painting style known as the 'court painting style' of Vraja or the Mughal style came to flourish besides the devotional style. The painting tradition continued to flourish in Vraja until the 17th century, when the iconoclastic excesses of Akbar's great-grandson Aurangzeb forced most Vaishnava communities, along with the community of artists affiliated to the temples, to emigrate to safer regions where tolerant Hindu rulers provided shelter. The practice of the arts including painting was carried on in the new surroundings, and the painting style of Vraja metamorphosed into a new tradition associated with the various stylistic schools of Rajasthani and Pahari painting.

North Indian miniature painting of the 15th/16th centuries was primarily and originally the property of the Vaishnava religion which at that time was at its peak. During this period, the musico-literary tradition of northern India, concentrated around Vraja as the principal devotional center, was significantly carried ahead by poet-saints such as Suradasa, Tulasidasa, Mirabai, Svami Haridasa and many others. Along with the musico-poetic practice, miniature painting too flourished in the devotional matrix. As a reaction to Muslim conquest and tyranny, especially during the period of the Delhi Sultanate and two centuries later under Aurangzeb, the oppressed Hindu society developed an extraordinary strength, which became reflected not at last in the consolidation of Vaishnava art on a large scale. A later change of subject-matters in Hindi poetry from devotional to erotic contents influenced the painting tradition whose thematic emphasis shifted in a parallel manner.

The North Indian or Rajput style of miniature painting developed and spread primarily in Rajasthan, leading to the formation of a number of independent styles linked to various places such as Kishangarh, Bikaner, Kota, Bundi and Jaipur. The Mewar style, on the other hand, occupies a special place within the North Indian painting tradition. This style preserved its original purity as it remained unaffected by the Mughal influence, the Mewar State having never been part of the Mughal empire. Based in and around Udaipur, the Mewar style of painting became closely associated with the Vallabhite Vaishnava tradition, whose principal devotional center had been shifted to Nathadvara near Udaipur following the invasion of Vraja by Muslim troupes under Aurangzeb. Consequently, devotional themes and in particular subject-matters pertaining to Krishnaite mythology feature particularly prominently in the Mewar style.

The second significant North Indian painting style of the post-16th century period, known as the Pahari style, was established by those artists who had sought refuge in the Hindu states of the Himalayan region. The principal Pahari schools of painting were affiliated to the regional centers of Tehri-Garhwal, Basauli, Kangra, Guler as well as Champa in Jammu. Like in the Rajasthani schools, in Pahari painting too the Krishnaite theme prevails, a fact that reveals the Vraja roots of the tradition.

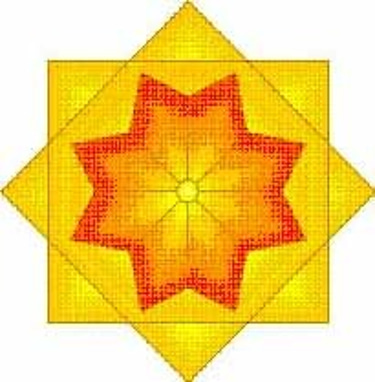

The same thematic focus is maintained by the Vraja style, the original painting tradition associated with the principal center of Vaishnava devotionalism during the 15th/16th centuries. One of the specialties in the Vraja style is the sañjhi paintings, a type of miniature painting which follows the exact structural outline of the sañjhi designs prepared in the Vaishnava temples of Vraja. A characteristic sañjhi design is prepared upon an octagonal earthen platform, housing a depiction of Lord Krishna or of the divine couple at its center, while an intricate layout of interlocked ornamental patterns in the outer spheres of the design symbolizes the expansion of divinity towards the eight directions. The sañjhi painting, prepared in watercolors on paper, gives permanent shape to the temporary designs made from dry colors for display on a single evening. Structurally, the sañjhi painting too places the divinity into the sanctum sanctorum at its center, with artful patterns extending towards the sides of the octagonal shape of the painting.

Like sañjhi and many other traditional art forms, miniature painting in Vraja style constitutes a nowadays rare art form with few exponents left. Every effort needs to be taken to preserve and promulgate this ancient art form in order to preserve this priceless treasure for generations to come.